Start a Search:

Author: Action Alliance

Dismantling Racism Resources

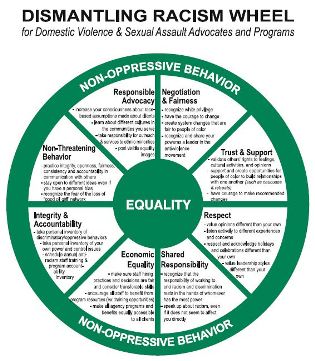

Two wheels created by the Women of Color Caucus and Social Justice Task Force of the Virginia Sexual and Domestic Violence Action Alliance. These wheels were created in the tradition of the Power and Control Wheel created by the Domestic Abuse Intervention Programs of Duluth, Minnesota. The Perpetuating Racism Wheel demonstrates how agencies might use power and control to perpetuate racism. The Dismangling Racism Wheel demonstrates how agencies can use principles of equaliaty to dismantle racism within their agencies.

Domestic Violence And Housing Stability: A Role For DV Programs

Within the DV movement, our dedication to that first and most elemental step—ensuring that there is a route toward safety—is reflected in our decades long commitment to building and protecting emergency shelter capacity. Yet today, some communities are implementing new service models less reliant on emergency shelter as survivors’ primary gateway to domestic violence advocacy and aimed instead at being more responsive to the specific needs of each survivor. And some shelters are closing their doors. Is this a sign that we are losing ground—or that we are becoming more flexible?

A change from the traditional communal living shelters, which are important and cherished programs, is gut-wrenching for many of us. However, in many ways it’s our success that has brought us to this important juncture as a movement and opened the way to a re-envisioning of the work ahead. Having created more avenues to basic safety in many communities, we can turn our focus to developing new approaches to assisting survivors who are still isolated from help or who need resources other than emergency services.

Click here to view this resource.

Domestic Violence Homicide Response Plan: A Toolkit for Domestic Violence Programs

Every survivor that domestic violence programs work with is a potential homicide victim. Advocates know this as they work with survivors, advocating on their behalf and building relationships with them and often their families. Domestic violence programs deal with the reality of knowing that a homicide could happen at any time, yet not allowing this knowledge to overpower their work with victims. When this most tragic violation occurs the traumatic impact is profound. This is felt by everyone - no matter the nature of their relationship with the victim. The needs of those closest to the victim, including their children, family and friends are of utmost importance. In addition, domestic violence programs, their clients and staff, and the communities they work within are deeply impacted. A homicide can change organizations and communities forever.

During this time, programs are asked to fulfill a variety of roles and often at the same time are dealing with their own sense of loss. An important part of responding and coping with these events is to realize there is no single “right” answer. Each of these tragedies is as unique as the human being whose life was taken, and all aspects of this person’s life and death need to be acknowledged, respected, and addressed as your program and community decide how to respond. It is also critical for the domestic violence program to utilize the tools and skills of trauma-informed care in their interactions with colleagues and others impacted by the death.

Produced by End Domestic Violence Wisconsin, the objective of this document is to provide a framework for domestic violence programs to develop a plan for how they will respond to a homicide in their community, whether the victim had been a client or not. Additionally, many of the elements of this plan can be adapted for use when programs experience a death of a client in shelter, as often the effects felt are similar.

Domestic Violence Toolkit for Mental Health Professionals

The Oregon Coalition Against Domestic & Sexual Violence (OCADSV) provides a toolkit for mental health professionals to better understand the links between mental health and domestic violence. It examines how DV is expressed and what that poses for those who are impacted by these forms of DV.

Don’t Ask, Can’t Report - A Practical Guide to Collecting Data on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender People in a Culturally Responsive Way

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people are included - but often invisible - in many evaluations. In light of increased federal attention to LGBT-specific data collection and the growing awareness of disparities faced by this population, evaluators must be prepared to consider how programs and policies affect LGBT people. However, evaluators are often at a loss for the best ways to ask about sexual orientation. Furthermore, we may inadvertently ask questions about gender in ways that marginalize transgender people, making them invisible to researchers and service providers. This skill-building workshop provided best practices for assessing sexual orientation and gender identity in youth and adult populations. Cutting-edge research on item development was shared, giving participants concrete ways to ask questions, and ways to make their evaluations more inclusive of sexual minorities.